In Turin on 3rd January, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six, Via Carlo Alberto. Not far from him, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and puts an end to the brutal scene, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words, ‘Mutter ich bin dumm‘ and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, cared for by his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse.

Even if we do not fully trust the apocryphal report of Nietzsche’s mental collapse, there are plenty of accounts about what happened to the German philosopher after 1889. What do we know about the horse and his owner? In A Torinói Ló (The Turin Horse in English), Béla Tarr and László Krasznahorkai use the story of the horse as an expedient to deliver a symbolic work of an overwhelming lyrical beauty.

The Turin Horse is, in the Hungarian film director’s own words, a representation of the heaviness of human existence. It comprises six long parts, corresponding to the six days of the narration. In the world of the film, every day is like the previous: the father gets dressed and undressed, the humble repast is consumed in silence, the daughter draws water from the well, and so on. The “Nietzschean shadow” of the visitor looking for palinka breaks the monotony on day three, by delivering a monologue that is dismissed as “rubbish” by the father. According to the visitor’s apocalyptic commentary, god and man are both the causes of the world’s destruction. The monologue is the only verbal key to the film’s interpretation. On day four, the arrival of a group of gypsies also constitutes a variation to the routine. In exchange for water, the daughter is given by the gypsies an “anti-Bible” — which is, actually, an original text by László Krasznahorkai, whose story the film is based upon.

The Turin Horse is, in the Hungarian film director’s own words, a representation of the heaviness of human existence. It comprises six long parts, corresponding to the six days of the narration. In the world of the film, every day is like the previous: the father gets dressed and undressed, the humble repast is consumed in silence, the daughter draws water from the well, and so on. The “Nietzschean shadow” of the visitor looking for palinka breaks the monotony on day three, by delivering a monologue that is dismissed as “rubbish” by the father. According to the visitor’s apocalyptic commentary, god and man are both the causes of the world’s destruction. The monologue is the only verbal key to the film’s interpretation. On day four, the arrival of a group of gypsies also constitutes a variation to the routine. In exchange for water, the daughter is given by the gypsies an “anti-Bible” — which is, actually, an original text by László Krasznahorkai, whose story the film is based upon.

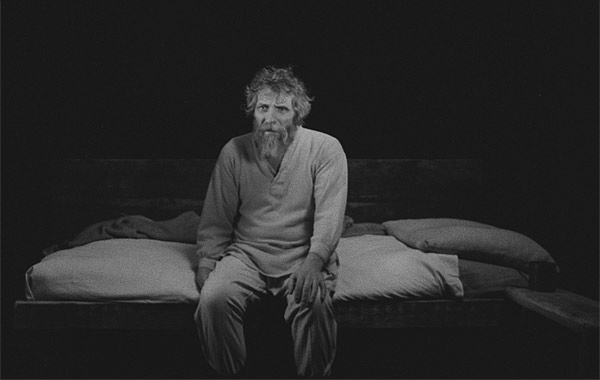

The father (János Derzsi) and his daughter (Erika Bók) — and the horse too, to an extent — are not ordinary characters; accordingly, they never give the impression to be role-constraint. Their interactions are sporadic and limited to a few repetitive actions, but they appear coherent and, in a way, natural — Béla Tarr confirmed in interviews that no screenplay was used as a reference for the filming. The camera moves around them, inspecting their environment while they carry on with their tasks or in the moments of stillness, offering every time different perspectives.

The black and white cinematography by Fred Kelemen is magnificent in its austerity. The opening sequence, with the camera lingering between horse and cabman as they are advancing among a misty and bleak countryside, is one of the most haunting ever seen on screen and it speaks more than volumes of philosophical speculations about the human condition. Overall, The Turin Horse is a metaphorical work in which every frame, carefully composed as a perfect picture in its own, hides a multiplicity of meanings. The camera always takes the time to allow the viewer to survey both space and gestures, even when minimal, without being forced into obvious considerations. The whole film is made of thirty long takes so that rather than being offered a clear-cut explanation, viewers are given the time to reflect and to come up with their own interpretation.

In The Turin Horse, Béla Tarr embraces and reinvents a certain visual iconography, including his own. References to master painters in the way the highly dramatic light is used and characters are framed are disseminated throughout the film. Light is, in particular, a powerful medium to provoke the spectator without the need to resort to obvious tricks of the trade, like dialogue and other intradiegetic elements. Just by following shadows forming on the characters’ faces, we can immediately place them in time and space and acknowledge their inner motives — or lack thereof.

The gale enveloping the house and the stable is expression of unfathomable forces at work in the world; whether it should be seen as a visible feature of the biblical God, it does not matter. Humans cannot help going on with their sinister play, while obscurity gradually enshrouds life. Not without reason, more than a critic compared The Turin Horse to Beckett’s Theatre of the Absurd.

The Turin Horse is Béla Tarr’s last film. Tarr always stated that rather than being an atheist he is a believer in the human dignity. Even if the film may seem to suggest otherwise, The Turin Horse is a work strongly rooted in this conviction. An intense testament to his filmmaking career.