Cheyenne is a retired rockstar. He lives in a big mansion in the suburban Dublin with his wife. He is bored, depressed and maladjusted. When his father, whom he has not spoken to in thirty years, is on his deathbed, he travels to New York to attend his final moments. Gaining unexpected insights on his parent’s life during his stay, Cheyenne embarks on a journey through the American continent to find his father’s torturer at the time of his Auschwitz’s confinement during WWII. Finding the man, a former SS officer by the name of Aloise Lange, now a US resident, has been Cheyenne’s father obsession until his death.

Cheyenne is a retired rockstar. He lives in a big mansion in the suburban Dublin with his wife. He is bored, depressed and maladjusted. When his father, whom he has not spoken to in thirty years, is on his deathbed, he travels to New York to attend his final moments. Gaining unexpected insights on his parent’s life during his stay, Cheyenne embarks on a journey through the American continent to find his father’s torturer at the time of his Auschwitz’s confinement during WWII. Finding the man, a former SS officer by the name of Aloise Lange, now a US resident, has been Cheyenne’s father obsession until his death.

The story unravels across a multiplicity of locations, from suburban Dublin to the aseptic expanses of New Mexico. Like in traditional tales, characters follow one another to influence the events; when they have exhausted their role, they disappear from the screen with no consequence. Likewise, as the main character from a traditional tale, Cheyenne describes a sort of circular path, from Ireland to the US and then back to Ireland again, from the initial unhappy equilibrium to a new one, in a soul-searching quest.

The first part of the film, that showing Cheyenne in his daily life as a retired rockstar, could have been a separate film. Given these premises, the rockstar’s American adventure feels a little preposterous. The film’s backbone, the life-long pursuit for vengeance, is the strongest element in Sorrentino’s work. It is also appropriate that this diegetic backbone never becomes the absolute focus, but it rather remains the underlying force in the film’s mechanics. That we have a super partes and apathetic character to unfold the core of the story for us is another point in favor. The motives behind Cheyenne’s father’s fixation for his former persecutor are almost futile, as it turns out; a man’s life is made of little facts, humiliations and misunderstandings: Cheyenne is on his own to figure life out also through hints unexpectedly collected from his father’s experience. In This Must Be the Place there are little episodes worth remembering, often those in which Sorrentino doesn’t try too hard to amaze the spectator, like the scene of the silent native American that has Cheyenne driving him to a spot in the middle of nowhere, or that in which Rachel’s son performs This Must Be the Place “by Arcade Fire” (ha!) for his parents–although his father’s presence is merely photographic–with Cheyenne’s accompanying him on the guitar. However, that is as far as the redeeming aspects go. Every other superimposed component it’s a superfluous adornment and takes away rather than add to the film’s strength and poignancy.

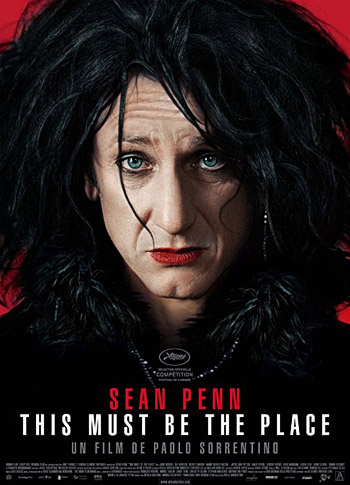

Characters are the hardest lump to digest. Not only Cheyenne, but all the characters are written and conceived as stereotypes: the weeping mother, the attractive Goth girl, the awkward young man who wants to date the Goth girl, the motherly but eccentric wife, the fat kid, the old Nazi criminal, and so on and so forth–heck, Sorrentino even finds a way to fit David Byrne in a cameo as himself. This Must Be the Place is definitely reminiscent of certain successful filmmaking exploits, such as those of the Coen bros (casting McDormand does not feel like a simple coincidence, either) and Wes Anderson in recent times. The difference is both the Coens and Anderson have the strong coherence that Sorrentino seems to lack, at least in this work. He winks at many different sources of inspiration–music and pop culture, mainly–taking a morsel from this and a detail from that, but he is unable to rearrange and translate them according to his personal vision. Outwardly, he models his Cheyenne after The Cure’s Robert Smith (make-up and hairdo, references to Smith’s hostility for flying, and so on) and takes on loan from other legendary artists of the New Wave music scene, like Virgin Prunes’ era Gavin Friday and Siouxsie Sioux. It is possible that Sorrentino wanted to mimic the effects achieved by comic artists, but what is an acceptable approach in comics does not necessarily work in films, unless it is adapted to be relevant to the medium. Sorrentino is a nostalgic and wants to pay tribute to a certain music scene, a certain culture, and a certain period of his life. It worked for Burton, couldn’t it work for him too? No, it doesn’t, because his attempt to give his characters a quirky flair remains a superficial one. The author gives us mere parody, but he does not offer to us the right material to reflect on the absurdity and irony of existence.

Acting is accordingly over the top–or if you wish under the top, in Sean Penn’s case. No actor in the film, with the only exception of Heinz Lieven as the ex-Nazi perhaps, tries to breathe actual life into the character. When the ending comes, we see Sean Penn going about the screen as himself and we cannot really tell why didn’t the ending come sooner: was the whole film a two-hour joke or a filmmaking exercise? No actual development appears throughout the story; in exchange, surrogate items to symbolize change are used lavishly.

Symbols are very trivial and are the means the author chooses make a point whenever subtlety would have been too complicated to achieve. An example is the cigarette prop. Mary’s mother in the first half goes through the trouble of telling Cheyenne why he has never taken to smoking despite his developing an addiction to a number of other vices. Cigarettes, she explains to him and to the viewers, is a grown-up thing and Cheyenne is a child at heart. When towards the end Cheyenne accepts to smoke his first cigarette after his introspective journey is complete, what this actually implies is definitely too literal. Another prop that similarly becomes symbol is the trolley, which is also banished from the ending. So is Cheyenne’s supposedly clownish appearance and deadpan demeanor.

The soundtrack to This Must Be the Place is another of the film’s sore points. There is the annoying tendency these days to use music to emotionally overcharge scenes, to the point of conveying the opposite message than that originally intended. Pop music is a language in its own and relying on it as a commentary is the most explicit way many young film directors find to grab their audience’s attention by pressuring its thirst for intense sensations. Sorrentino falls prey to this tendency and goes far overboard with it. He chooses his soundtrack carefully, with the precise purpose in mind to have it supply his film with easy to grasp metaphors and explanations to everything. Is it a wonder then that he entrusts Arvo Pärt with some of the most highly emotional scenes of the film? Pärt is one of these composers that many purists and critics like to hate, and with a reason. Although listened to in moderation and with the right disposition it’s impossible to deny the magnificence and refinement of some of his works, Pärt is already loaded with easy emotional weight: to add to his notes a graphic counterpart would be overkill. Not only Sorrentino has Spiegel Im Spiegel playing in the background coupled with off-camera voice repeatedly, but he also employs slow motion and drowns the footage in soft magic hour tones to make us feel as strongly as we can the melancholic beauty of the moment. I mean, really: how can an experienced filmmaker that wants to be taken seriously conjure anything like that? Not even a clueless film student that doesn’t know any better would consciously devise something so decadent. Not satisfied yet, Sorrentino packs the film with songs from the likes of Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy and Talking Heads. Jónsi & Alex may have offered the less intrusive contribution with their discreet track.

Paolo Sorrentino and his collaborators crafted a film of remarkable visual and technical quality. The camera is handled with mastery and cinematography is superb. Too bad that they couldn’t manage to put more than skill in this work. Their purpose remain weak and confused, aesthetic exaggerations and continual parody aim at concealing the many flaws in character and story development.

Had the occasion to watch the movie at a smaller scale event and I am OK with it, though I don’t see this as a memorable movie either. I cannot agree with the whole review, but I agree with some of it.

I agree with you about the abuse of music by Arvo Part in soundtracks. I think Part is one of the most overvalued composers of the actual contemporary music, and her influence in listeners , like the influence of others ” neo-spiritualists” composers, like Gorecki, Sumera, Kancheli, Tuur,Silvestrov,etc ,is funest. My personal experience with this composers is a way that begins in emotion and finally ends in boredom, although all they have some fascinating works.Is the same thing that happened some years ago, when every ” prestigious” director wanted to have in the soundtracks of their movies some notes of Philip Glass ( in USA ), and Michael Nyman ( in UK and Europe), without asking themselves if this is the best or most appropiate choice to their movies.But , you know, this is a “prestigious” choice. A mode, after all.Now ,every time I hear a young composer speak about their deep influence of Part or Gorecki, I begin to have suspiscions about the value of their music.And when they spoke of the influence of Glass and Nyman , I begin to tremble.And yes, you are right: today too many directors play all their cards in the ” shocking” subjects of their movies, forgetting everything except the desire to shock the audience at any prize.No actors, no script, no photography…,only two or three ideas to sustain a two hours film.

Eventually I might see it, but I guess it’s not worth making a big effort to seek it out.