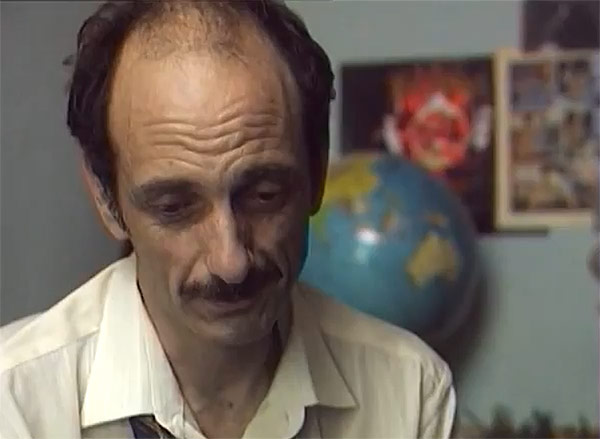

7 May 1986 is a date to remember for Romania. Like most of his comrades and fellow countrymen, the little bureaucrat named Iulica Ploscaru (Gabriel Spahiu) sheds a tear when the Steaua Bucharest defeats Barcelona, after an epic penalty shootout during the European Cup final in 1986. Helmuth Duckadam has become a national hero after saving four penalty shots in a row. Duckadam’s exploits are the talk of the day, but for people working at the same factory where Iulica is employed there is not enough time to fully savor Duckadam’s feats. The celebrations for the anniversary of the glorious Socialist Republic of Romania are the current priority and Iulica and his comrades are preparing a special show for the festivity. However, they could never imagine the following hours of their lives would become unforgettable for other unforeseen reasons.

Achim’s work offers a down-to-earth and stark depiction of Communist Romania in the 80’s: he and his crew faithfully recreated for the screen places, atmospheres and lifestyle of the period.

Visul Lui Adalbert (Adalbert’s Dream in English) is a complex work that lends itself to different interpretations and layers of analysis. The story is minimal and summing it up doesn’t really tell anything relevant about the film-maker’s intentions. Adalbert’s Dream deals with the question of collective responsibility and deception, both on a private and public level. Gabriel Achim relies on the artifice of the film within a film to get his point across, although to get the message as a whole the viewer has to wait till the very last minute of the story. Several keys to decode the actual message are offered throughout the picture, but they’re buried among apparently aimless trivialities and character blabbering.

For a coincidence, Adalbert’s Dream reminded me of another Romanian film, Aurora by Cristi Puiu, which was screened at RIFF last year. Like Aurora, Adalbert’s Dream is a slow paced film, conceived at the same time as an essential and convoluted work, where revealing details are used only sparingly and whose purpose only becomes intelligible when all elements come together at the end. Differently from Puiu’s film though, Achim’s film works harder at confusing the spectator. Whereas Puiu had the advantage of silence, the massive presence of futile dialogue in Visul Lui Adalbert tends to exhaust and conceal meaningful information from the audience, instead of conveying a sense of realism as it may seem on a superficial level. Characters constantly use dialogue to deceive themselves and others and to remove crucial questions from their individual and collective conscience. Similarity among the regime’s deceptions and those carried out by Iulica and his comrades is evident, although not easily given away by the plot. What is real and what is fabrication? Why is man so eager to submit himself to the power of subterfuge, lie, hypocrisy? Who is truly responsible, the deceiver or the deceived? The ending comes abruptly to clear the viewer’s doubts.

Visul Lui Adalbert is one of the films in competition for the Golden Puffin award 2011.