I won’t deny that, leafing through the festival’s program, I was honestly surprised to find that a film about Paul Watson would be screened at RIFF 2011. My surprise comes from the fact whaling is a taboo topic in Iceland and, whenever it is brought up, it always provokes very strong feelings, both among the pro and the against party. Unless you are talking to somebody that doesn’t really care either way, you will meet with passionate opinions on the subject, and with passionate I don’t mean also legitimate. The Icelandic fishing and whaling lobbies retain to this day powers that, in some instances, go well beyond their rightful authority. The practice of whaling is still carried out not only by Iceland, but also by the neighboring Faroe Islands, Greenland and Norway; more notably whaling is still pursued by Russia and Japan. As a matter of fact, most of the meat whale produced yearly by Iceland is sold to the Japanese market. In countries like Faroe Islands or Greenland and, to some extent, also Iceland, whaling is well-rooted in the cultural tradition and, even if anachronistic, it is regarded as part of the local customs.

Dolman’s Eco-Pirate follows Paul Watson in his anti-whaling activist career, from his very beginnings as Greenpeace co-founder to his exploits as Sea Shepherd’s captain.

Canadian animal rights activist and environmentalist Paul Watson, captain and founder of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, is best known for being a controversial figure: for some Watson is a role model, for others a dangerous personality with extreme egocentric tendencies. Raised in the small fishing town of St. Andrews-by-the-Sea in New Brunswick, Watson was the oldest of seven children. Son to a dysfunctional father, he was raised together with his siblings by his mother alone. Since his childhood, Watson demonstrated deep interest for nature and, in special way, for animals. In 1969, Watson joined anti-nuclear movements in Vancouver, which led him to enter in contact with a group of people with different backgrounds that had come together to take action against environmentally damaging practices. During the 70’s, the group, which later went by the name of Greenpeace, widened their scope, including whaling and other issues in their campaigns. After a promising start together, Paul Watson’s acts became too reckless for Greenpeace to support. Greenpeace’s philosophy had always maintained a moderate and non-violent approach; Watson was of the opinion that Greenpeace’s way of dealing with environmental protest was not really going to change the state of things. Eventually, both sides realized that further collaboration was impossible and Paul moved on to found his own organization in 1977.

According to Watson’s biocentric point of view, on average man feels no real empathy for animals and nature and, when he does, he’s just moved by selfish standards and thus he is totally oblivious of nature’s true needs and intentions. Organizations like Greenpeace and other bland forms of protest are, in Watson’s view, either too submissive or far from being truly aimed at the well-being of the world that surrounds us. We condemn and take a stand when abuse and violence are perpetrated against children, women or other members of our society, and yet we allow the same violence to be committed against nature and animals. Man’s idiocy, if not contained and opposed, will ultimately cause his own destruction. From this perspective, Watson’s extreme measures to fight whaling and injustice against animals are essentially a necessity. Violence is an integral factor in revolutions and Watson’s revolution is no exception.

According to Watson’s biocentric point of view, on average man feels no real empathy for animals and nature and, when he does, he’s just moved by selfish standards and thus he is totally oblivious of nature’s true needs and intentions. Organizations like Greenpeace and other bland forms of protest are, in Watson’s view, either too submissive or far from being truly aimed at the well-being of the world that surrounds us. We condemn and take a stand when abuse and violence are perpetrated against children, women or other members of our society, and yet we allow the same violence to be committed against nature and animals. Man’s idiocy, if not contained and opposed, will ultimately cause his own destruction. From this perspective, Watson’s extreme measures to fight whaling and injustice against animals are essentially a necessity. Violence is an integral factor in revolutions and Watson’s revolution is no exception.

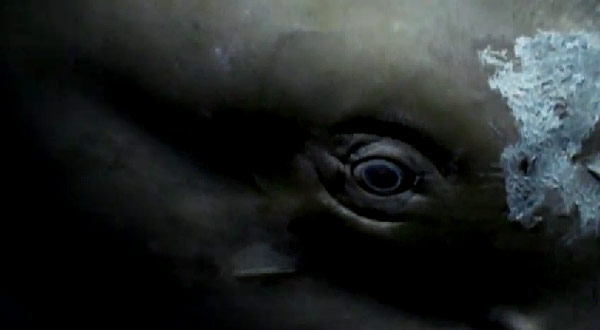

Dolman’s documentary contains strong images: an unforgettable look at the wide open eye of a dying whale, baby seals slaughtered in cold blood in front of their mothers, the chaotic mess of a post-whaling massacre, sharks being mutilated for their valuable fins. Dolman delivers Watson’s message in a little less than two hours, combining interviews, scenes from onboard Sea Shepherd’s ships and archival footage. Detractors may argue that the film is solely expression of a biased point of view, offering no real objectivity on Watson’s character. Voices from the opposition are not absent from the film, but admittedly, it’s definitely not in the least flattering for the pro-whaling party to be represented by Japan’s spokesman Joji Morishita, who awkwardly compares making use of natural resources, animals included, to drawing funds from a bank account.

If you want to know more about Paul Watson and Sea Shepherd or if you want to support them in their battle, you can visit the organization’s official page here.

The great problem with this kind of movies ( this one ,or “The cove” by Louie Psihoyos and “Earthlings”by Shaun Monson) is that they played all their cards in the same terrene ,the emotional one ,forgetting a more reflexive and intellective approach.The directors don”t want to make think the spectators but are only searching for new adepts to his cause, and for that ,everything is allowed.At last ,like in the disgusting Italian shockmumentarys of the seventies (I think in people like Antonio Climati, Mario Morra and Romano Vanderbes),they only left in the memory of the spectator a handful of shocking images to incite an emotional,manipulated ,non-critical answer in the spectator, in the name of good feelings and good intentions.Not to mention the cinematographical poverty of this kind of films: aesthetically speaking,they are dead,and here we are talking about cinema and art.In any case , is a sign of maturity to show a movie like this in an Icelandic film festival.

I completely agree with you. However, as you say, cinema is an art and art usually chooses the emotional approach rather than the intellectual one. Unless we are takling about avant-garde and something for the intelligentsia, most art will speak to people’s guts rather than to their brains. Also, cinema is mostly about entertainment, so as a film-maker or as a producer you have to consider what the greatest part of your audience will be looking for when they sit through your film. Most of them wouldn’t stand to be “educated” by something that bores them out of their minds, that doesn’t speak their language, that doesn’t come with information that is easy enough to process while eating their popcorn, just as they wouldn’t normally pick an essay to be “educated” when they read a book. Finally, cinema is a business and if we are speaking big numbers, there are chances you have to go for this type of approach to make sure your film is a successful product.

Good for Iceland to show a on this question. The more people is informed, the more they can decide for themselves.

*a movie