Last Train Home by Canada-based director Fan Lixin is a poignant but accurate depiction of the lives of over 130 million Chinese migrant workers. The film took years to complete and it represents in a straight to the point manner how our contemporary economies are destined to fail, if not from a merely financial point of view – which is what happened with the 2008 world crisis – at least from a moral or ethical one.

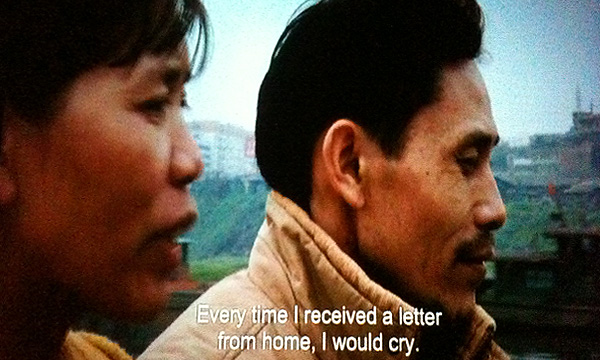

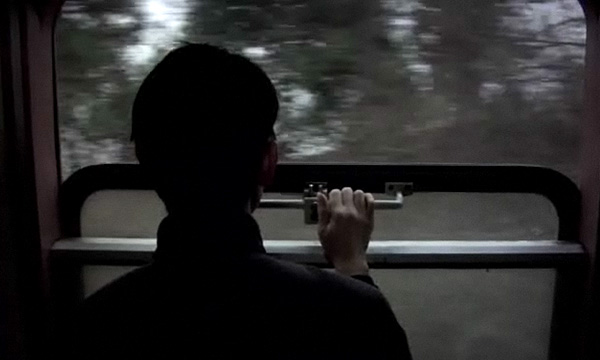

Qin’s parents have been migrant workers for more than sixteen years. They were forced to leave the countryside in the 90’s because they had no means to support their family. They moved to the city and applied as unskilled labor in Guangzhou. They’ve been working in a textile factory since then, sending home every penny they earned, hoping to provide their offspring with the adequate education to grant them a more satisfactory future. Qin and Yang, her little brother, have been raised by their grandparents in the countryside, where only the old and the young, both unable to work, can live. Many young people around the age of Qin though are more and more often forced to move to the city themselves, to help their own families to make a living. Only once every year those migrant workers, older and younger alike, are permitted to go home to see their families and share a few days in their hometowns among their loved ones: during the Chinese New Year’s celebrations. For this reason, being able to catch the train home has become for many of them the single reason that keeps them going. Even if it means undergoing sufferings and deprivations of every species, even if it could seem catching that train isn’t really worth it, that became the very reason that keeps their life worth living.

“If the family can’t even spend the New Year together life would be pointless,” one – a man like many others – affirms.

Qin is young and she feels neglected by her parents. She doesn’t like school and she sees all her friends one by one leaving to go look for fortune in the city. At some point she leaves too, causing her family – her parents that had high hopes regarding her future especially – great despair. Her position is probably result of the sort of rebellion that is commonplace status of teenagers everywhere. But in her case the conflict leading her to take the same path of her parents has the bitter taste of total defeat, not only on a private level, but also on a larger scale.

Many young people like Qin choose every year to work when they’re still underage in order to conquer freedom. Economical freedom is in their eyes equal to happiness. But what kind of freedom is that? Isn’t that freedom only a mirage supported by a system which tends to exploit workers? Isn’t that freedom in reality a form of slavery which deprives individuals, especially of younger generations, of the desire to access means of self-improvement necessary to be free in the real sense of the word? China is in many cases only an accomplice, not the only culprit, for this state of things affecting its population. Western economies, relying so heavily on underpaid labor from Eastern countries for keeping their services and goods competitive on the world market, are also to blame. But then we – the audience – are to blame too, as we are all part of the vicious mechanism perpetrating misery on a global level.

The Western viewers, who seem to be the main recipients of the film’s message, should be lead to put their hands on their hearts and carefully think about implications of the state of things heavily induced by Western exploitation of poorer economies. The reality of families like Qin’s one are factual examples of how this exploitation can inflict damage to the existence of millions of fellow human beings. Is it really worth it? Shouldn’t we find more progressive means in order to guarantee wellness on a world scale? Do we really want to keep on maintaining and trusting a system like the capitalistic one, which proved to be inadequate even for the world’s richest countries, a system fattening the pockets of those who are already well-off, creating enormous gaps between citizens that have to struggle everyday to improve their miserable conditions? The answers to these questions would of course be cliched for anybody with a conscience. Whatever the outcome, it’s the poor and the unfortunate who will suffer, not the wealthy. The same old problem is that those ruling the masses and impoverishing them day in, day out are those who have no conscience at all.

Title: Last Train Home

Year: 2009

Director: Lixin Fan

Genre: Documentary

Country: Canada, China, United Kingdom

Runtime: 85 minutes

Language: Mandarin

I found it quite revealing that Qin’s sentiments parallel the sort of teenage/young-adult culture obsessed with materialism, enamored with a disposable income and the superficial glamour of “the city life” that runs prominent throughout the developed world.

This is an especially dangerous phenomenon for the youth of China who may resign to contentment in a labor-intensive environment and ultimately limited lifestyle, with very few opportunities for advancement.

Though the parents have the best of intentions to ensure some sort of future for their children and their family, their absence contributes to the dismantling of Confucian values of filial piety and strong emphasis on education.

But their absence is not entirely to blame. As the stench of capitalism continues to permeate throughout China, the labor of Qin’s family, as well as many families, will not only endanger family cohesion, but will inadvertently perpetuate a system of exploitation where only the consumers and corporate fat-cats (within China as well as the Western world) benefit.

Very true, and anyway exporting sentiments from the “developed world” is also part of the picture as the system conceived it.